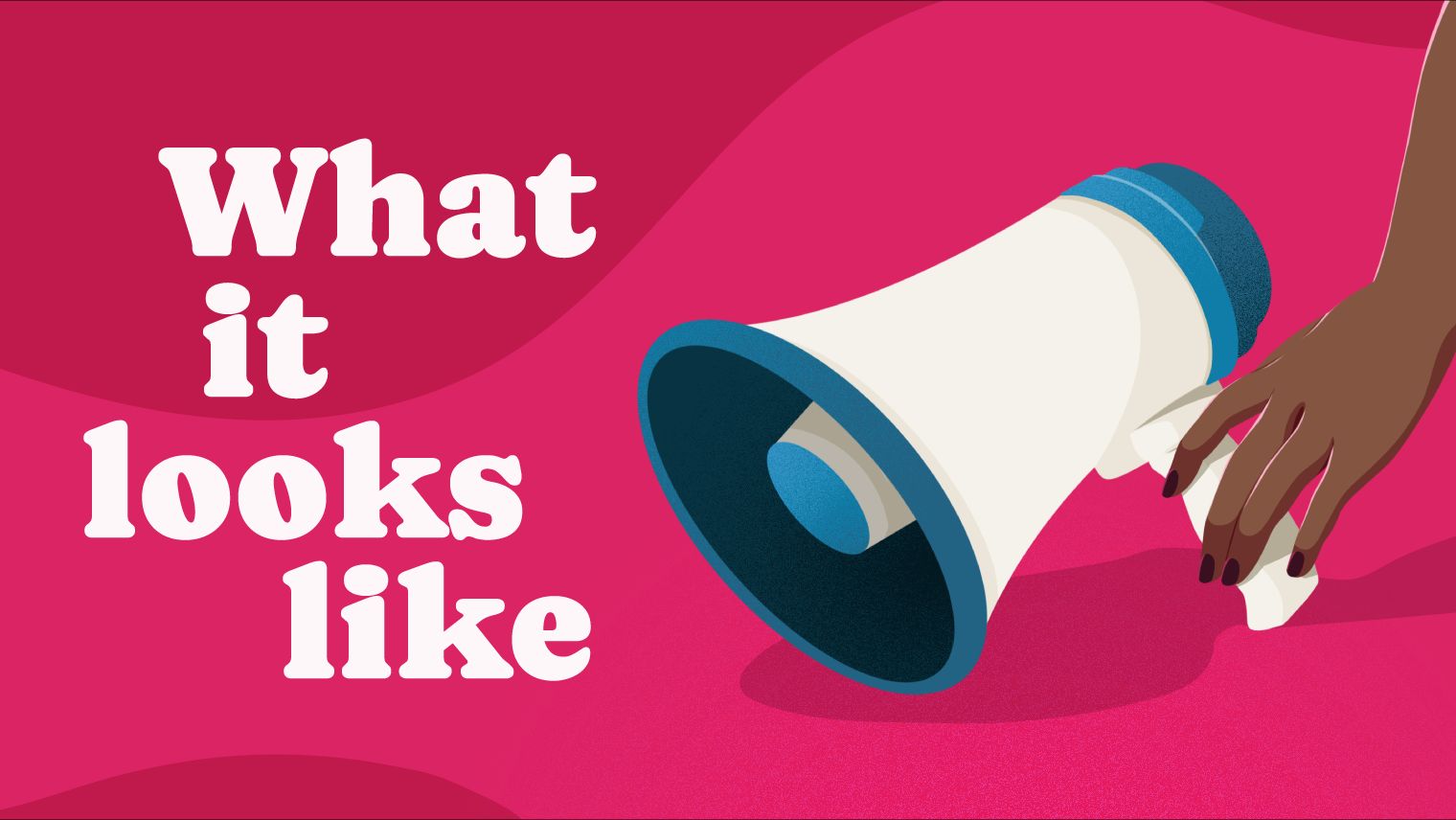

Advocating for Myself and Others: Double Mastectomy, DIEP Flap Reconstruction

April 15, 2025

Illustration by Brittany England

- Procedures: double mastectomy, DIEP flap reconstruction

- Reconstruction immediately postmastectomy: no

- Years of procedures: 2022 and 2024, 2 years apart

- Age: 37 years old

- Race or ethnicity: Black

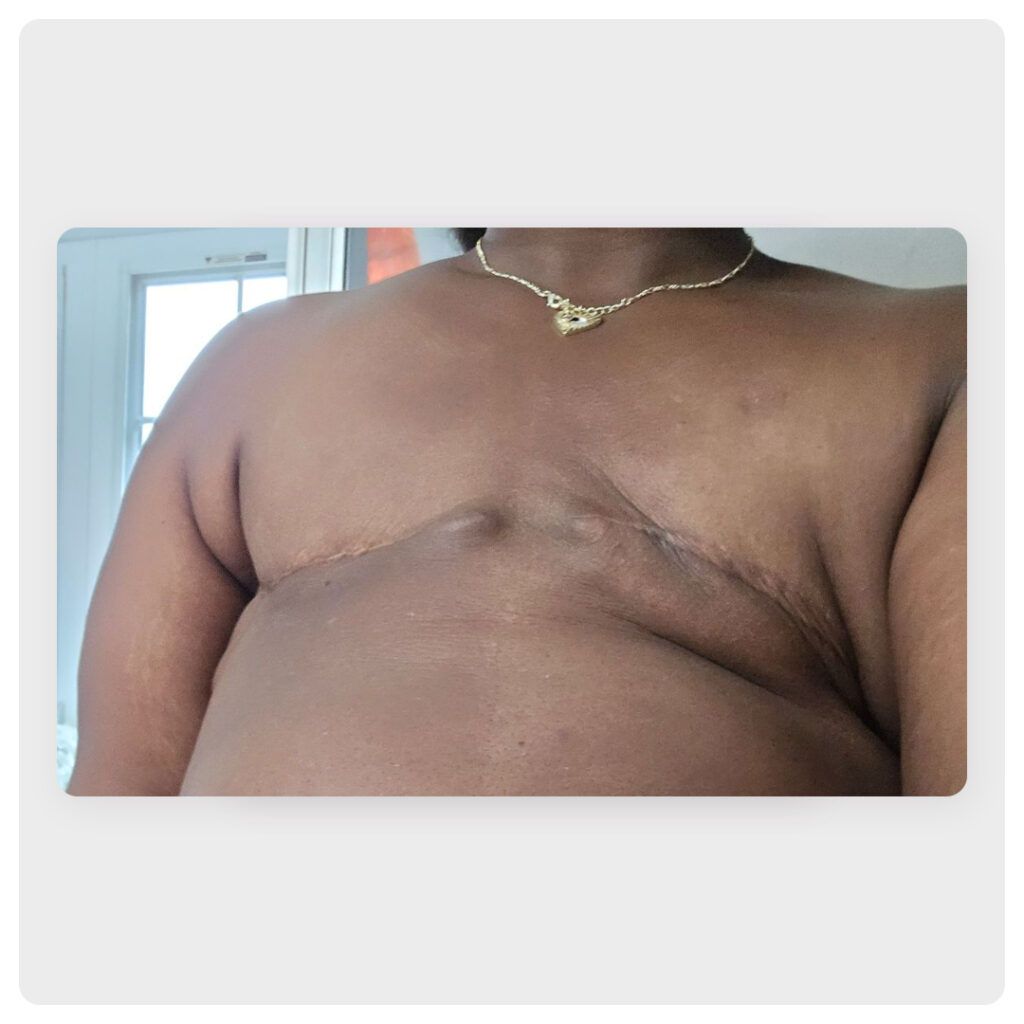

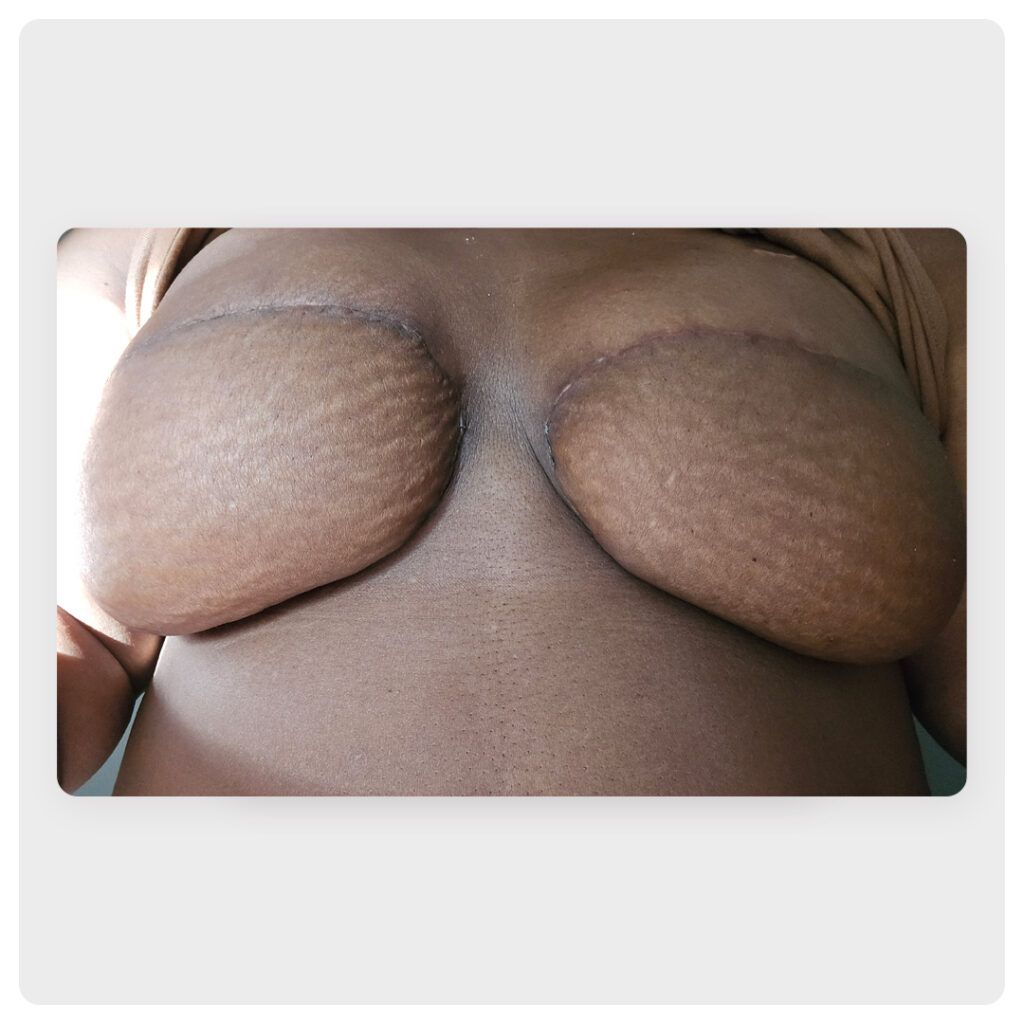

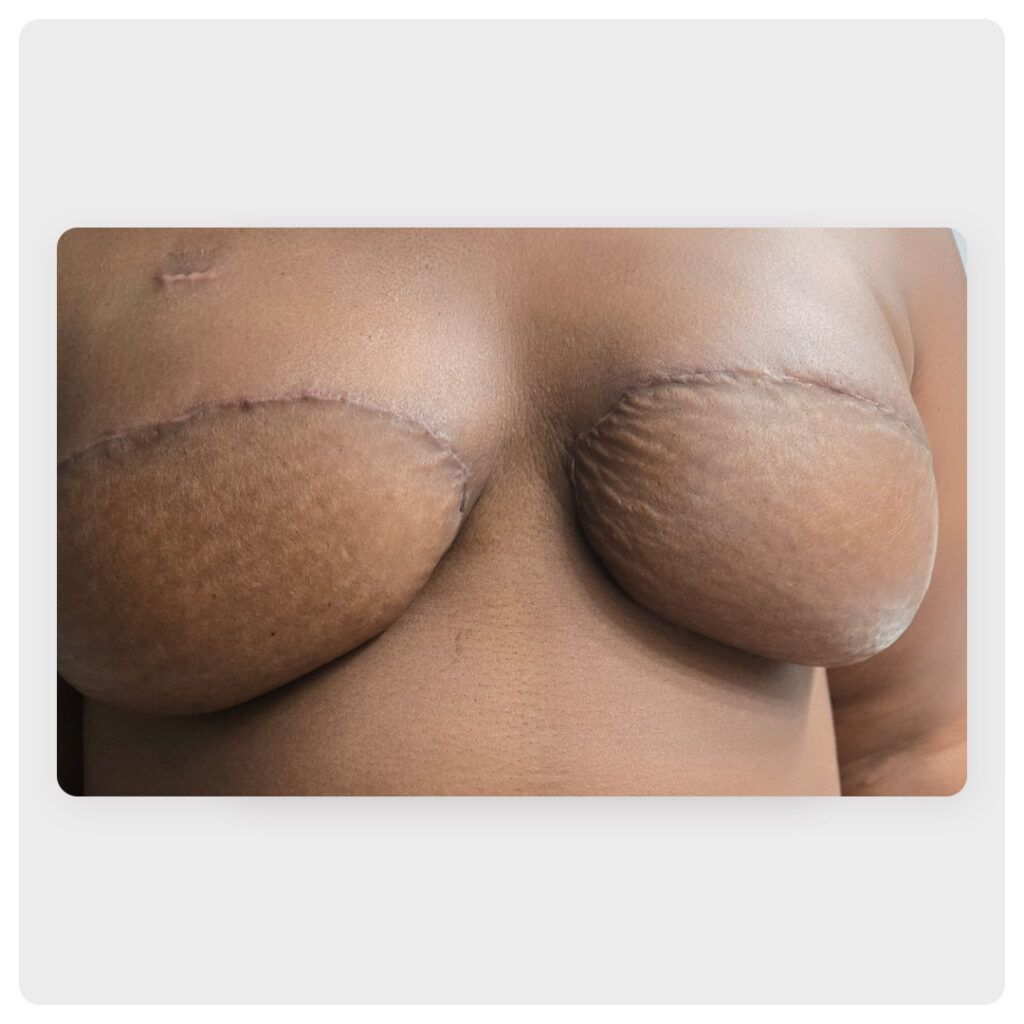

This article contains graphic, intimate images of a postsurgery body. The photos have been generously shared by a breast cancer survivor so that others can benefit from uncensored visual information that may help them make important surgical decisions for themselves.

In July of 2021, I was 36 years old and had just finished nursing my baby when I felt a lump during a self-breast exam. Initially I thought it was just a breastfeeding milk cyst, but it persisted for a couple of weeks, so I went to get a mammogram and sonogram.

When I arrived at the imaging facility, the radiologist said, “You’re too young to have a mammogram. You’re only 36. You don’t need to have a mammogram done.”

There was a lot of back and forth, and I had to advocate to get the mammogram. Then, when I did, the radiologist misread the study. He read it as a galactocele, which is usually a benign milk cyst. At the time, I didn’t think much more because I had just finished breastfeeding. I had no known family medical history and no known genetic factors of breast cancer.

My text message diagnosis

A couple of days later, I got a call from another radiologist who examined my scan and said the margins looked suspicious in the findings and recommended a biopsy. I was pretty nervous at that point, but I went ahead and got the biopsy.

I was told I’d receive a phone call with my biopsy results, but when the following Monday came, I didn’t receive a phone call. Instead, I received a text message with my cancer biopsy results.

I found out that I got cancer through a text message — it was devastating.

I’m a PA (physician assistant) specializing in emergency medicine, and I was working in the ER at the time. I had to leave my patients because I was upset and in disbelief. I didn’t believe the results. I thought it was an error, but I couldn’t get in touch with the physician to confirm anything until the following morning.

When they called me the next morning, the radiologist was pretty cut and dry. He said, “Yeah, you have cancer. This is triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) invasive carcinoma. You’ll receive a phone call from a nurse navigator.”

I asked to verify that the results were mine. I thought someone must’ve made an error in the lab. He said, “No, these are your results.” It was the worst time of my life.

Facing treatment challenges

I received my first chemo treatment on August 25, 2021. I had 16 rounds of neoadjuvant chemo (chemotherapy given to shrink the tumor before further treatment) initially.

I wanted to enroll in a clinical trial but when I asked my oncologist about it, he dismissed me. I’m a healthcare professional by trade, so I’d find my own clinical trials and email them to him. But he just wasn’t interested in enrolling me.

During my treatment, I faced even more adversity because I wasn’t prescribed Keytruda, which is an immunotherapy that has been approved for some TNBC.

Around midway between my chemo treatments, I questioned my oncologist as to why I hadn’t received it. He turned his computer to me and said, “Well, it wasn’t on my checklist. So, that’s the reason why you didn’t get it.” This was pretty devastating, and I decided to part ways with that oncologist. I felt like he didn’t have my best interest at heart.

Advocating my way to better care

I told my nurse navigator what was going on and asked her for some recommendations — she’d been available and hands-on throughout my treatment process. She recommended another doctor to establish care with, and that’s what I did.

When I started working with my new oncologist, I expressed interest in joining a clinical trial. Within two weeks of establishing care with her, we enrolled me in a trial at Georgetown.

It was important for me to be part of clinical trials because I have three daughters, and they’re young right now. If I contribute to clinical research with my specific DNA, it can help move the needle forward to help prevent them from developing breast cancer in the future.

Before starting the trial in August of 2022, I continued on and received 16 rounds of chemo. I responded pretty well to the chemo. My tumor had shrunk from around 5 1/2 centimeters (cm) all the way down to 1 cm. I finished my last round of chemo in January 2022, and then I had a double mastectomy with flat closure in March 2022.

After the double mastectomy, I started 30 rounds of radiation over 6 weeks in the summer.

When I joined the trial in August of 2022, I received more chemo and immunotherapy, which I should’ve received the first time around. Because I was so advanced, I still needed oral chemo regardless. I had to receive another 6 months of chemo pills, and I had to do immunotherapy every 3 weeks through my port.

I finished my last cancer treatment of chemo and immunotherapy in April of 2023. Thus far, I’ve been cancer-free.

My path to reconstruction was filled with obstacles

I consulted with multiple plastic surgeons in my insurance network. After doing some research on implant complications, I knew I wanted to have my own tissue reconstruction.

All of the plastic surgeons I consulted with advised against having breast reconstruction right away because I still needed to undergo radiation. They were concerned that having tissue expanders during radiation would lead to complications.

So, I had a flat closure. But I was not happy about the aesthetic outcome — it was horrible.

I couldn’t look at myself in the mirror for a very long time. I felt disfigured and ugly. For 2 1/2 years, I lived with a flat closure and wore heavy prosthetic bras.

My doctors didn’t inform me that to qualify for reconstruction after radiation, I’d have to meet certain BMI standards. I couldn’t lose the amount of weight that they pressured me to lose in the specified amount of time. It was depressing and caused me to develop body dysmorphia.

Finding the right surgeon for my DIEP flap reconstruction

Finally, I found a phenomenal surgeon in Texas named Dr. Elisabeth Potter. She was the first surgeon who told me I could have DIEP flap reconstruction. She’s highly specialized and does a lot of DIEP flap reconstructions every week. She doesn’t have the same guidelines as some other, more old-school surgeons.

After 2 1/2 years of waiting to have breasts again, I had surgery with her on December 9, 2024. I had to go to Texas for that, and I’m still in recovery now, but I’m doing OK.

I found Dr. Potter through The Breasties organization. I saw her speak and started following her on Instagram. I saw she’d posted that she doesn’t have BMI cut-offs. I started looking at her research and a gallery of her work. I liked that she advocated for women with legislation to help make sure insurance covers breast reconstruction. She is a true badass in the field and helps women in many ways.

Not only did Dr. Potter give me breasts. I had a big hernia and a separation of my abdominal muscles, called diastasis recti, which measured about 10 cm. She closed all that up and removed tissue from my stomach to make breasts out of my own tissue.

I am grateful for Dr. Potter. She has changed my life. I feel like a woman again! No woman should have to experience what I went through.

The recovery hasn’t been easy, but I thought it would be much worse. My pain levels have been pretty tolerable. I’ve stopped taking pain meds, but my abdomen is still sore.

My husband has been my rock through all this, ensuring I have everything I need. I had a friend come help me out as well.

Advocating for the underrepresented

I share my story with others so they know they are not alone — my experience may resonate with someone else.

Coming from a medical background, even though I’m not in the oncology field, I was shocked by what I experienced trying to navigate my care. I hate to say this, but I believe I faced a lot more adversity because I am a Black woman.

If I hadn’t had the advantage of a medical background to investigate different medical research methods, would I have received the right care? That experience made me want to become an advocate, to speak for women who are underserved and underrepresented so they can have a voice, too.

You have to be your own advocate. And if something doesn’t feel right, speak up about it — don’t be intimated by a doctor’s credentials or titles. You’re the captain of your ship, which is your body, and they’re the co-captains to help you get to the finish line.

You also need to make sure you know your disease like the back of your hand so that you can have the power to understand what you’re battling.

Finding support for the psychological battle

Mental health is just as important as physical health because battling cancer is a huge psychological battle. Seek out resources. My safe haven has been Touch The Black Breast Cancer Alliance, and I’m a community advisory member with that group. They have resources and support groups to educate women of all backgrounds about their bodies and the disease. They offer support for Black women, Brown women, and Latino women.

We’ve also developed a website called Black TNBC Sanctuary, where you can see what double mastectomies look like on people who look like you, which isn’t easy to find. It’s important to have that representation.

My life has changed dramatically since my diagnosis. I look at things differently and am more appreciative of life. I try to keep my stress levels down as much as possible and love my family harder. I seize the day and live every moment to the fullest.

Bezzy BC and Young Survival Coalition are partnering to create What It Looks Like, a series showcasing photographs of different breast reconstruction choices on bodies of all shapes, sizes, and colors.

We’re spotlighting the breast reconstruction decisions of people who have had breast cancer so that other people facing mastectomy surgery can see and hear about many different real-life outcomes.

If you’d like to share your reconstruction (or flat closure) images and story, we’d love to hear from you. Just have your photos ready and fill out this submission form.

Images and stories will be anonymously published on BezzyBC.com.

Medically reviewed on April 15, 2025

1 Source

Like the story? React, bookmark, or share below:

Have thoughts or suggestions about this article? Email us at article-feedback@bezzy.com.

About the author